Fragment de connaissance

Om

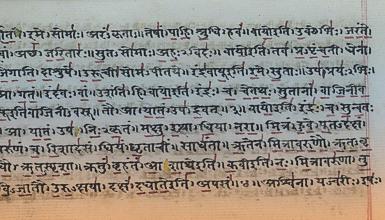

pUrNamadah pUrNamidaM

pUrNAt pUrNamudacyate

pUrNasya pUrNamAdAya

pUrNamEvAvashiSyate

Om

That is whole; this is whole;

From that whole this whole came;

From this whole, thiat whole removed,

All what remains is whole.

ॐ पूर्णमदः पूर्णमिदं पूर्णात्पुर्णमुदच्यते

पूर्णश्य पूर्णमादाय पूर्णमेवावशिष्यते ॥

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥

Om Puurnnam-Adah Puurnnam-Idam Puurnnaat-Purnnam-Udacyate

Puurnnashya Puurnnam-Aadaaya Puurnnam-Eva-Avashissyate ||

Om Shaantih Shaantih Shaantih ||

Meaning:

1: Om, That is Full, This also is Full, From Fullness comes that Fullness,

2: Taking Fullness from Fullness, Fullness Indeed Remains.

3: Om Peace, Peace, Peace.

Om

Purnam-adah Purnam-idam

Purnat Purnam-udacyate

Purna-shya Purnam-adaya

Purnam-eva vashisyate

Om

[adah] refers to the unknown, the unknown in the sense of the not-directly known due to remoteness, and [idam] refers to the

immediately perceivable known.

Traditionally, however, idam has come to have a much broader meaning. [idam] is stretched to stand for anything available for

objectification; that is, for any object external to me which can be known by me through my means of knowledge. In this sense, [idam], this, indicates all [driSya], all seen or known things. [idam] can be so used because all [adah,] all things called ’that’ become ’this’ as soon as their thatness, their remoteness in time, place or knowledge is destroyed. It is in this sense that the SantipAta "pUrNamadah" uses [idam].

The first verse of IshAvAsyOpaniSad, following the SantipATa makes clear that idam is used in the traditional sense of all driSya, all

known or knowable things:

idam sarvam yat kinca jagatyAm jagat

all this, whatsoever, changing in this changing world..

Verse 1,

ISAvAsyOpaniSad

Given this meaning, idam, this swallows up all ’that’s’ subject to becoming ’this’; in other words, idam stands for all things capable

of being known as objects. So when the verse says pUrNam idam, "completeness is this", what is being said is that all that one knows or is able to know is pUrNam.

This statement is not understandable because pUrNam means completeness, absolute fullness, wholeness. PurNam is that which is

not away from anything but which is the fullness of everything. If pUrNam is total fullness which leaves nothing out, then ’this’ cannot

be used to describe pUrNam because ’this’ leaves something out.

What? The subject. ’This’ leaves out aham, I, the subject. The world ’this’does not include I. I, the subject, is always left out

when one says ’this’. If I am not included then pUrNam is not wholeness. Therefore, pUrNam idam appears to be an untenable

statement because it leaves out I.

Adah, That

What about the other pronoun, adah, that? What does adah mean in context? Does ’that’ have a tenable relationship with pUrNam? Since idam, this, has been used in its traditional sense of all knowable objects, here or there, presently known or unknown, the only meaning left for ’that’ is to indicate the subject. Idam, this, stands for everything available for objectification. What is not available for

objectification? The objectifier - the subject. The subject, aham, I, is the only thing not available for objectification. So, the real

meaning of the pronoun adah, that, as used here in contrast to idam, this, is aham, I.

However, it was said that adah, that, indicates a jnEyavastu, something to be known; in other words, something not yet directly

known because it is remote from the knower in time, place or in terms of knowledge. If that is so, how can adah, that, mean aham, I? Am I remote? I am certainly not remote in terms of time or place. I am always here right now. But perhaps I may be remote in terms of knowledge. If in fact I do not know the true nature of myself I could be a jnEyavastu, a to-be-known, in terms of knowledge.

Because it is only through the revelation of shruti (scripture functioning as means of knowledge) that I can gain knowledge of my true nature, it can be said that in general the truth of aham is remote in terms of knowledge - something that is yet to be known.

So in context, adah, the pronoun ’that’, stands for what is meant when I say, simply, "I am", without ay qualification whatsoever.

’That’ so used as ’I" means AtmA, the content of truth of the first person singular, a jnEya-vastu, a to-be-known, in terms of knowledge.

When that knowledge is gained, I will recognize that I, AtmA, am identical with limitless Brahman - all pervasive, formless and

considered the cause of the world of formful objects.

So far, then, the first two lines of the verse read:

PUrNam adah - completeness is I, the subject AtmA, whose truth is Brahman, formless, limitlessness, considered creation’s cause;

PUrNam idam - completeness is all objects, all things known or knowable, all formful effects, comprising creation.

PurNam, Completeness

The statement, "Completeness is I, the subject" on its face dos not seem any more tenable than the statement, "Completeness is all

objects." Both statements seem to suffer from the same kind of defect. Each looks defective because it fails to include the other.

Moreover, each looks like it could not include the other; and, pUrNam, completeness, brooks no exclusion whatsoever.

If aham, subject, is different from idam, object; if idam, object, is different from aham, subject, if pUrNam, to be pUrNam, cannot be

separate from anything, then the opening lines of the verse seem not to be sensible. But this conclusion comes from failure to see the two statements as a whole from the standpoint of pUrNam. To find sense in the lines, do not look at pUrNam from the standpoint of aham, I, and idam, this, but look at aham and idam from the standpoint of pUrNam. The nature of pUrNam is wholeness, completeness limitlessness. There cannot be pUrNam plus something or pUrNam minus something. It is not possible to add or to take away from limitlessness. The nature of pUrnam being what is, ’that’ pUrNam must include ’this’ pUrNam; ’this’ pUrNam must include ’that’ pUrNam.

Therefore, when it is said that aham, I, am pUrnam and idam, this, is pUrNam, what is really being said is that there is only pUrNam.

Aham, I, and idam, this, traditionally represent the two basic categories into one or the other of which everything fits. There is

no third category. So if aham and idam, represent everything and each is pUrNam , then everything is pUrNam. Aham, I is pUrNam which includes the world. Idam this, is pUrNam which include me. The seeming differences of aham and idam are swallowed by pUrnam - that limitless fullness which shruti (scripture) calls Brahman.

If everything is pUrNam, why bother with ’that’ and ’this’? Is it just poetic license to make a riddle out of something which could be

stated simply? It seems an unnecessary confusion to say ’that’ (Which really stands for aham - I) is pUrNam and then to say ’this’

(Which really stands for all the objects in the world) is pUrNam when one could just describe the fact and say: everything is pUrNam.

PurNam is absolute fullness; absolute fullness is limitlessness which is Brahman.

Why not such a direct approach? Because it would not work; it would only add to confusion, not clear it. Although such simple statements are a true description of the ultimate fact, to communicate that fact so that it can be seen as true, something else must be taken into account. What? Experience. My everyday experience is that aham, I, am a distinct entity separate and different from idam jagat, this world of objects which I perceive. My experience is that I see myself as not the same at all as idam, this. When I hold a rose in my hand and look at it, I, aham, am one thing and idam, this rose I see, is quite another. In no way is it my experience that I and the rose are the same. We seem quite distinct and separate. Because shruti tells me that I, aham, and the rose, idam, both are limitless fullness, pUrNam. I may come up with some logic that says, "Therefore I must include the rose and the rose must include me’ but that logic does not alter my experience of the rose as quite separate from me.

Furthermore, it is not my experience that either I or the rose are, in any measure, pUrNam, completeness - limitless fullness. I seem to me to be totally apUrNah, unfull, incomplete, inadequate, limited on all sides by my fellow beings, by the elements of nature, by the lacks and deficiencies of my own body and mind. My place and space are very small; time forever crowds me; sorrow dogs my path. I can find no limitless fullness in me. No more does there seem to be limitless fullness in this rose even now wilting in my hand, pressed by time, relinquishing its space; even in its prime smaller and less sturdy than the sunflowers growing outside my window. It is my constant experience that I, aham, and all I perceive, idam, are ceaselessly mutually limiting one another.

Based on one’s usual experience, it is very difficult to see how either aham, I or idam, this can be pUrNam; and, even more difficult

to see how both can be pUrNam.

PurNam, completeness, absolute fullness, must necessarily be formless. PurNam cannot have a form because it has to include

everything. Any kind of form means some kind of boundary; any kind of boundary means that something is left out - something is on the other side of the boundary. Absolute completeness requires formlessness. Sastra (scripture) reveals that what is limitless and

formless is Brahman, the cause of creation, the content of aham, I.

Therefore, given the nature of Brahman by shruti, I can see that pUrNam is another way for shruti to say Brahman. Brahman and pUrnam have to be identical; there can only be one limitlessness and that One is formelss pUrNam Brahman.

Thus, the verse is telling me that everything is pUrNam. PurNam has to be limitless, formless Brahman. But when I look around me all that I see has some kind of form. In fact, I cannot perceive the formless. The only things I can perceive are those which I can

objectify through one of my means of perception. Objectification requires some kind of form. How then can it be said that idam, this,

which stands for all objectifiable things is pUrNam - is formless?

It is easier to accept the statement that adah, that, which refers to aham, I, is pUrNam, has no form. Upon a little inquiry, it

becomes apparent that the nature of adah which stands for the ultimate subject, I, has to be formlessness. The ultimate subject

can have no form because to establish form there would have to be another subject, another I to see the form - the other I would then become the ultimate subject which if it had a form would require another subject, which would require another subject, which would require another subject, endlessly, in a condition called anavastA, lack of finality. But, this is not the case. Adah does not stand for a state of anavastA, but for an ultimate being. Sastra reveals and inquiry confirms that the essential nature of the ultimate

subject, I, is self-luminous; "I" is self-proving formless being.